Ethan Hawke, Peter Dinklage, Winona Ryder, Sam Rockwell, Natasha Lyonne and many more.

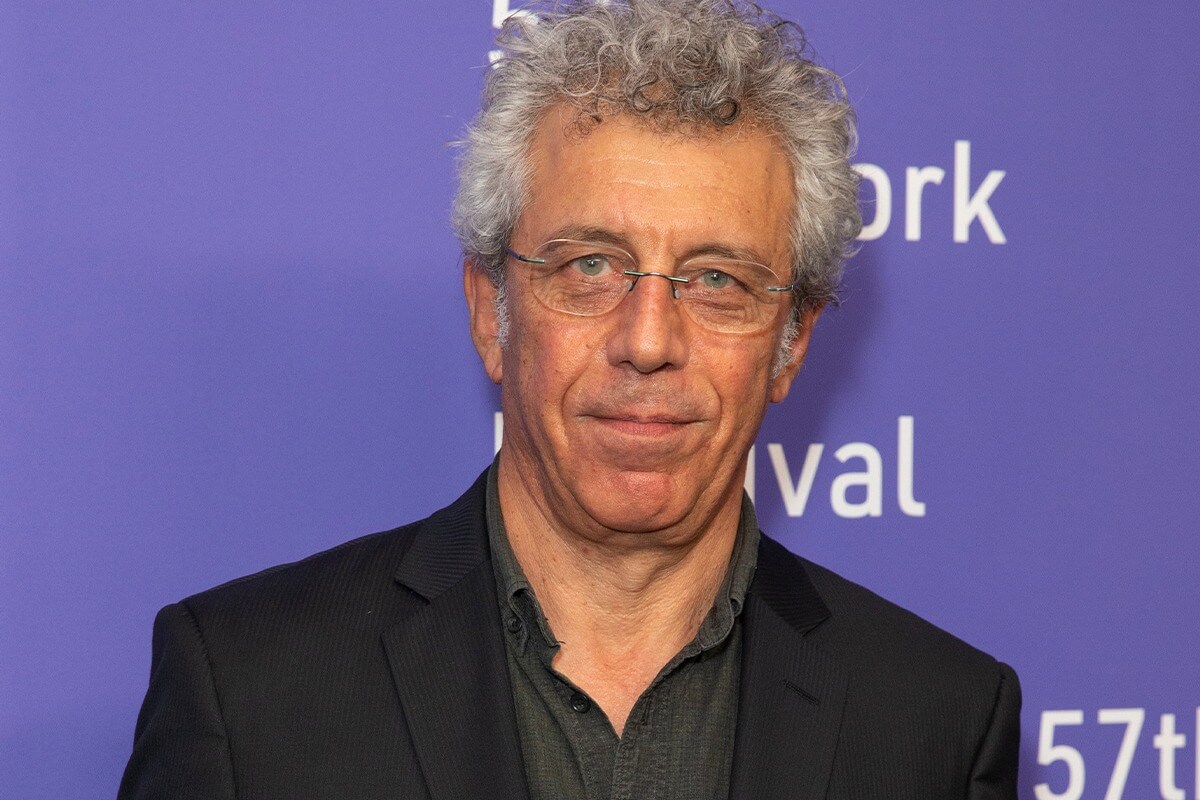

In 2014, playwright-novelist-actor Eric Bogosian published a book titled “100 (monologues),” featuring a collection of monologues he had originally performed as part of his six off-Broadway solo shows. Indeed, three of his plays, Drinking in America, Pounding Nails in the Floor with my Forehead, and Talk Radio, received Obie Awards, and one earned a Drama Desk Award. Recognized as an innovative and provocative artist, Bogosian wrote two plays, subUrbia and Talk Radio which went on to be adapted to motion pictures. As a performer, audiences will recognize Bogosian as Captain Danny Ross on Law & Order: Criminal Intent, Gil Eavis in Succession, and Arno in the crime thriller Uncut Gems.

When first releasing “100 (monologues)” Bogosian asked his acting buddies if they’d like to record themselves performing his monologues to complement his book, to serve as an inspiration to actors who are always on the lookout for quality monologue material. Presently, Theatre Communications Group has posted a bounty of celebrated thespians performing Bogosian’s monologues on 100monologues.com. Actors, and the otherwise curious, are invited to come check out the emotional, poetic, witty monologue performances. The collection serves as a great resource to gain insights and draw inspiration from talents such as Michael Shannon, Jennifer Tilly, Ajay Naidu, Brian D’Arcy James, Richard Kind, Elizabeth Rodriquez, Alison Wright, Sebastian Stan, Vincent D’Onofrio, Billy Crudup, and Michael Stuhlbarg.

Audition monologues are an efficient way for casting directors to quickly become acquainted with actors, observe their type, assess their present level of skill, and learn what kinds of roles they most relate to. However, some monologue practices have the potential to interfere with casting’s ability to view actors in their best light and can be distracting and confusing. For example, while some casting directors are okay with props such as cell phones, a coat, or pen, many agree that a prop should only be used if it’s absolutely essential to the content of the scene.

On “100 (monologues),” Michael Laurence performs with a cigarette and a drink in his hand, and Alison Wright and Betty Gilpin likewise interact with props. Being able to observe these choices allows actors to assess what works and what detracts from the work.

Which actors chose to sit during the monologue, and which opted to stand? While sitting during a monologue can work out quite well, certain performances seem a little stifled when performed seated.

Observe if any of the actors mime during their performances. Miming has the potential of turning the act into a game of charades: Did he slam a door or swat a fly? But if miming is essential, actors are advised to keep it brief to keep the piece moving forward.

Where is the actor focusing their eyes during the performance? Are they looking straight at the camera? If speaking to someone, do they appear to be talking randomly to the air or did they choose a focal point to represent the character with whom they’re speaking? Is the actor’s face easy to see even when he or she is turning to speak to a character, or is only a profile visible to the viewer?

Are the actors rushing their deliveries or taking their time, demonstrating they understand the artistry of the material? How much subtle emotion can be observed and is there clarity in their speech? These kinds of details allow actors to fully connect with the material and audience rather than rushing past the good stuff.

An authentic performance centered on subject matter the actor genuinely cares about is powerful to watch. Most importantly, whatever creative decisions the actor makes, the goal is to maintain the focus right where it belongs—on the performance. Focusing on a truthful, authentic performance allows the rest to fall right into place.